Emmitt Till By AJ

Emmit Till was like any other ordinary boy. He lived in Chicago in 1955 with his mother. But this summer he was going to visit his Uncle Mose who lived down south. Down south and Chicago were totally different. First of all, you couldn't go to a school with someone that wasn't your color, you couldn't go to any bathroom you wanted and couldn't eat where you wanted. In other words, it was segregated. Now, let me get back to my story. "I can't wait till go I down south. I wonder what it will be like."said Emmit. "I think you'll like it, but stay out of trouble ya hear. "said Emmit's mom. "Ok. "said Emmit. The next day Emmit arrived. He met up with his Uncle Mose and went straight to his Uncle's house. "So how old are you now?" said Uncle Mose. "Fourteen." said Emmit. "So, yah like fried chicken? "said Uncle Mose. "Yeah" said Emmit. "Good cause thats what we having for dinner"said uncle Mose So they had dinner and Emmit went to bed.The next day Emmit went outside to go meet some new friends, but he took his junior high school graduation picture with him. A few minutes later he met two boys named Tony and Stacey. Emmit said, "Look at my class picture." Tony said, "Why are there white people in your class?" Emmit said, " I don't know. Why don't you?" Stacey said, "They aren't allowed in our school." Tony said, "Since you hang around white people so much, I dare you to go talk to that white lady in that store." Emmit said, "Ok." So Emmit went to the candy store and bought candy. He paid for it and before he left he said "Bye baby." to a white woman in the store and then her husband came running after him, but Emmit was too fast and he ran all the way home. That night Uncle Mose asked Emmit, "What did you do today ?" "Who me?",said Emmit "Yes you." said Uncle Mose. "Oh ummm, well ummm, I made some new friends", said Emmit. "Why are you so nervous?" said Uncle Mose. "Why ya say that Uncle Mose?" asked Emmit. "Well, ya stuttering." said Uncle Mose. "Is that why well I'm cold and I'm shivering?" said Emmit. " Cold in Alabama? You must be sick or something because I'm sweating", said Uncle Mose. "Well I'm tired so I'm going to bed."said Emmit. "Ok, see yah in the morning."said Uncle Mose. But Uncle Mose didn't know that Emmit was going to be kidnapped that night. In the middle of the night two men came and kidnapped Emmit. They drove him to the Hallatachie River. First, they beat him up with a bat and then they got 75 lbs bag of cotton gin, tied it around his ankle with barb wire , and threw him in the river Afterward they had a trial about the Emmit Till case. Those two men were found innocent. Emmit's family had two other trials and they were still found innocent. The reason why those two men were found innocent was because it was the 1950's and it was segregated and the trial had an all white jury.

Emmitt Till By by Khaled and Chris

Emmett Till lived in Chicago and was visiting Mississippi which was a segregated state. He was black and said "bye baby" to a white lady. During the night, the white lady's husband and husband's brother took him to a barn and beat him up. Then they threw Emmett into a river. In court the two men confessed that they had killed Emmett Till but were not convicted.

August 28, 1955: Emmett Till Murdered

http://www-dept.usm.edu/~mcrohb/html/cd/till.htm

Till, a Chicago youth visiting Mississippi relatives for the summer, was killed by Roy Bryant and J.W. Milan in Money, MS. The two took Till from the home of his elderly uncle under the pretense of teaching him a lesson for whistling at a white woman (Bryant's wife), a violation of one of the segregated South's sacred taboos. Bryant and Milan apparently took the youth to a nearby barn where they beat him mercilessly. They then shot him several times, tied him to the fan of an old cotton gin, and dumped him into the Tallahatchie River. This brutal killing brought national and international attention to the Magnolia state. Despite this coverage and the overwhelming evidence against them, the jury pronounced the murderers "NOT GUILTY." Rather than retarding the movement, this incident helped to galvanize black Mississippians into action.

Mississippi Trial, 1955

Chris Crowe

Annotation

In Mississippi in 1955, a sixteen-year-old finds himself at odds with his grandfather over issues surrounding the kidnapping and murder of a fourteen-year-old African American from Chicago.

Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till REPRINT

Stephen J. J. Whitfield

Synopsis

Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old black youth from Chicago, was lynchedin Mississippi in 1955 after he allegedly made overtures to a white woman. His white killers were acquitted. The author seeks to examine the case in the context of the civil rights struggle and American social problems. Bibliography. Index.

Lynching of Emmett till: A Documentary Narrative

Christopher Metress (Editor)

Lynching of Emmett till: A Documentary Narrative

Christopher Metress (Editor)

From the Publisher

At 2:00 A.M. on August 28, 1955, fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, visiting from Chicago, was abducted from his great-uncle's cabin in Money, Mississippi, and never seen alive again. When his battered and bloated corpse floated to the surface of the Tallahatchie River three days later and two local white men were arrested for his murder, young Till's death was primed to become the spark that set off the civil rights movement.

With a collection of more than one hundred documents spanning almost half a century, Christopher Metress retells Till's story in a unique and daring way. Juxtaposing news accounts and investigative journalism with memoirs, poetry, and fiction, this documentary narrative not only includes material by such prominent figures as Hodding Carter, Chester Himes, Eleanor Roosevelt, James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Eldridge Cleaver, Bob Dylan, John Edgar Wideman, Lewis Nordan, and Michael Eric Dyson, but it also contains several previously unpublished works--among them a newly discovered Langston Hughes poem--and a generous selection of hard-to-find documents never before collected.

Exploring the means by which historical events become part of the collective social memory, The Lynching of Emmett Till is both an anthology that tells an important story and a narrative about how we come to terms with key moments in history.

Remember Emmett Till?!

http://personal.mia.bellsouth.net/atl/i/c/icim/emmett.htm

August 1955: Missing for three days, Emmett Till's body was found in the Tallahatchie River. Expressing horror at the criminal brutality, whites thought blacks would not complain. While visiting relatives in Mississippi, Emmett was beaten to a pulp, shot through the head and thrown into the river by Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam. Local lawyers refused to defend them. Insisting justice would be done, the media and public officials proclaimed, "all decent people were disgusted with the murder."

Emmett's mother, Mamie Bradley shipped Emmett's body to Chicago, where she held an open-casket funeral so "all the world could see what they did to my son." Thousands of blacks across the country heard about the case and were horrified by pictures published in Jet Magazine.

Labeled a lynching, the sheets came off and five prominent lawyers defended Milam and Bryant. Whites supported the murderers. Only blacks came forward as witnesses. Defense Attorney John Whitten told the all white jury, "Your fathers will turn over in their graves if Milan and Bryant are found guilty and I'm sure that every last Anglo-Saxon one of you has the courage to free these men in the face of that outside pressure."

In Emmett's mother's words, "Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something happened to the Negroes in the South I said, 'That's their business, not mine.' Now I know how wrong I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all." Source: http://www.watson.org/emmett.htmlmailto:lisa@www.watson.org

Wolf Whistle

Lewis Nordan

Synopsis

"The wolf whistle of the title comes from Bobo, a black teenager from Chicago visiting in Arrow Catcher, Mississippi. Directed at the wife of the town's most prominent white resident, this whistle soon leads to Bobo's murder. {This novel is} based on the Emmett Till lynching, which occurred near Nordan's hometown in 1955." (Libr J)

Annotation

Nordan twists the outline of real events into an altogether new shape within which a teacher conducts a magical mystery tour of the mid-20th century American southern ethic. "No writer since Flannery O'Connor has better captured the nuances of white trash culture."--North Carolina Independent.

From the Publisher

Born and raised in the Mississippi Delta, novelist Lewis Nordan was fifteen years old the summer two white men from the next town were tried for the murder of a black boy who wolf-whistled at a white woman. The boy's name was Emmett Till and the year his murderers were tried (and acquitted) was 1955. In the thirty-eight years since, that white adolescent's impressions of what happened in Money, Mississippi, have been turned over in Nordan's mind and memory. In the turning, those impressions have gathered the odd outgrowths and distortions of this writer's truly wild imagination. The outlines of real events have been subsumed into entirely new and different shapes. The result is Wolf Whistle, a novel starring a Mississippi white-trash girl named Alice who understands - in her heart - the meaning of evil. Alice is the fourth-grade teacher at the Arrow Catcher Elementary School and she yearns to teach her pupils things worth learning. She believes the best way to do it is with field trips. The first trip of the 1955 school year is to the bedside of the fourth-grader's terminally burned classmate, Glenn Gregg. (Glenn got in the way of a gasoline fire he set to burn up his despicable daddy.). The final trip is to be to the courthouse where Alice and her fourth grade class attend the murder trial of Glenn Gregg's despicable daddy, Solon, and his employer, Lord Montberclair, whose wife's beauty is what inspired a black teenager's reckless compliment ("Hubba, hubba"). In between those two educational forays, Nordan takes the reader on a field trip of his own - along the crooked paths of righteous racism and violence that lead to the courthouse gallery where the reader joins Alice and her fourth graders to witness the 1950s American Southern ethic at work. Soft heart turned "bleeding heart," it is Alice in whom the germ of guilt recognition grows, matures, and bears fruit to pass on to future generations of white southerners. It is inside Alice's brilliant heart that Lewis Nordan has come of age as a novelist.

http://www.watson.org/~lisa/blackhistory/early-civilrights/emmett.html

In August 1955, a fourteen year old boy went to visit relatives near Money, Mississippi. Intelligent and bold, with a slight mischievous streak, Emmett Till had experienced segregation in his hometown of Chicago, but he was unaccustomed to the severe segregation he encountered in Mississippi. When he showed some local boys a picture of a white girl who was one of his friends back home and bragged that she was his girlfriend, one of them said, "Hey, there's a [white] girl in that store there. I bet you won't go in there and talk to her." [15] Emmett went in and bought some candy. As he left, he said "Bye baby" to Carolyn Bryant, the wife of the store owner.

Although they were worried at first about the incident, the boys soon forgot about it. A few days later, two men came to the cabin of Mose Wright, Emmett's uncle, in the middle of the night. Roy Bryant, the owner of the store, and J.W. Milam, his brother-in-law, drove off with Emmett. Three days later, Emmett Till's body was found in the Tallahatchie River. One eye was gouged out, and his crushed-in head had a bullet in it. The corpse was nearly unrecognizable; Mose Wright could only positively identify the body as Emmett's because it was wearing an initialed ring.

At first, local whites as well as blacks were horrified by the crime. Bryant and Milam were arrested for kidnapping even before Emmett's body was found, and no local white lawyers would take their case. Newspapers and white officials reported that all "decent" people were disgusted with the murder and proclaimed that "justice would be done." [16]

The Emmett Till case quickly attracted national attention. Mamie Bradley, Emmett's mother, asked that the body be shipped back to Chicago. When it arrived, she inspected it carefully to ensure that it really was her son. Then, she insisted on an open-casket funeral, so that "all the world [could] see what they did to my son." Over four days, thousands of people saw Emmett's body. Many more blacks across the country who might not have otherwise heard of the case were shocked by pictures of the that appeared in Jet magazine. These pictures moved blacks in a way that nothing else had. When the Cleveland Call and Post polled major black radio preachers around the country, it found that five of every six were preaching about Emmett Till, and half of them were demanding that "something be done in Mississippi now." [17]

Whites in Mississippi resented the Northern criticism of the "barbarity of segregation" and the NAACP's labeling of the murder as a lynching. [18] Five prominent lawyers stepped forward to defend Milam and Bryant, and officials who had at first denounced the murder began supporting the accused murderers. The two men went on trial in a segregated courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi on September 19, 1955.

The prosecution had trouble finding witnesses willing to testify against the two men. At that time in Mississippi, it was unheard of for a black to publicly accuse a white of committing a crime. Finally, Emmett's sixty-four year old uncle Mose Wright stepped forward. When asked if he could point out the men who had taken his nephew that dark summer night, he stood, pointed to Milam and Bryant, and said "Dar he" -- "There he is." Wright's bravery encouraged other blacks to testify against the two defendants. All had to be hurried out of the state after their testimony.

In the end, however, even the incredible courage of these blacks did not make a difference. Defense attorney John C. Whitten told the jurors in his closing statement, "Your fathers will turn over in their graves if [Milam and Bryant are found guilty] and I'm sure that every last Anglo-Saxon one of you has the courage to free these men in the face of that [outside] pressure." The jurors listened to him. They deliberated for just over an hour, then returned a "not guilty" verdict on September 23rd, the 166th anniversary of the signing of the Bill of Rights. The jury foreman later explained, "I feel the state failed to prove the identity of the body." [19]

The impact of the Emmett Till case on black America was even greater than that of the Brown decision. For the first time, northern blacks saw that violence against blacks in the South could affect them in the North. In Mamie Bradley's words, "Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something happened to the Negroes in the South I said, `That's their business, not mine.' Now I know how wrong. I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all." [20] Blacks, in the North as well as in the South, would not easily forget the murder of Emmett Till.

http://www.heroism.org/class/1950/heroes/till.htm

The Lynching of Emmett Till

The horrific death of a Chicago teenager helped spark the civil rights movement

In the summer of 1955, Mamie Till gave in to her son's pleas to visit relatives in the South. But before putting her only son Emmett on bus in Chicago, she gave him a stern warning:

"Be careful. If you have to get down on your knees and bow when a white person goes past, do it willingly."

Emmett, all of 14, didn't heed his mother's warning. On Aug. 27, 1955, Emmett was beaten and shot to death by two white men who threw the boy's mutilated body into the Tallahatchie River near Money, Mississippi.

Emmett's crime: talking and maybe even whistling to a white woman at a local grocery store.

Emmett's death came a year after the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawed segregation. For the first time, blacks had the law on their side in the struggle for equality. Emmett's killing struck a cord across a nation. White people in the North were as shocked as blacks at the cruelty of the killing. The national media picked up on the story, and the case mobilized the NAACP, which provided a safe house for witnesses in the trial of the killers. Emmett became a martyr for the fledgling civil rights movement that would engross the country in a few years.

Mamie Till spoke out about her son's death. She held an open-casket funeral for her son, so that the world could see "what they did to my boy." Emmett's face was battered beyond recognition and he had a bullet hole in his head. The body had decomposed after spending several days underwater.

Roy Bryant, whose wife Carolyn was the white woman at the store, and his half brother, J.W. Milam, were tried for Emmett's murder and acquitted by a jury of 12 white men.

There are conflicting reports as to what Emmett said to Carolyn Bryant, who owned the store with her husband. By most accounts, Emmett and his cousin Curtis Jones, who was visiting from Chicago as well, were playing with other boys outside the store. Emmett pulled a picture of a white girl out of his wallet and boasted to the other boys that she was his girlfriend. The other boys seemed to think it was just bragging by a city boy from the North. But one boy suggested to Emmett go inside the store and talk to the white woman who was running the cash register, especially if he was so good with white women.

Emmett went inside, and by some accounts he whistled at Carolyn Bryant, who was 21 at the time. Others said he bought some gum and made a lewd suggestion to Bryant on the way out. Bryant testified at the trial that Emmett grabbed her and said, "Don't be afraid of me, baby. I been with white girls before."

In the segregated South, punishment for a black male who made a sexual suggestion a white woman was swift. Word got around about what had happened and Emmett's relatives suggested he get out of town as fast as possible.

He didn't leave fast enough. According to historian David Halberstam, Ron Bryant and Milam tracked Emmett down and pulled him from his uncle's house. The beat him but Emmett was unrepentant. So, they decided to kill Emmett to make an example of him. They took him to the river and made him strip down naked. "You still better than me?" Milam asked Emmett. "Yeah," the boy said. Milam shot him in the head. They tied Emmett's body to a cotton gin fan and dumped it into the river.

Unfortunately, Emmett's killing was only one of thousands of similar murders in the South, and his name is not well-known. But the case was an important turning point in America's civil rights struggle.

From: http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/emmetttill.html

"Twas down in Mississippi no so long ago,

When a young boy from Chicago town stepped through a Southern door.

This boy's dreadful tragedy I can still remember well,

The color of his skin was black and his name was Emmett Till.

Some men they dragged him to a barn and there they beat him up.

They said they had a reason, but I can't remember what.

They tortured him and did some evil things too evil to repeat.

There was screaming sounds inside the barn, there was laughing sounds out on the street.

Then they rolled his body down a gulf amidst a bloody red rain

And they threw him in the waters wide to cease his screaming pain.

The reason that they killed him there, and I'm sure it ain't no lie,

Was just for the fun of killin' him and to watch him slowly die.

And then to stop the United States of yelling for a trial,

Two brothers they confessed that they had killed poor Emmett Till.

But on the jury there were men who helped the brothers commit this awful crime,

And so this trial was a mockery, but nobody seemed to mind.

I saw the morning papers but I could not bear to see

The smiling brothers walkin' down the courthouse stairs.

For the jury found them innocent and the brothers they went free,

While Emmett's body floats the foam of a Jim Crow southern sea.

If you can't speak out against this kind of thing, a crime that's so unjust,

Your eyes are filled with dead men's dirt, your mind is filled with dust.

Your arms and legs they must be in shackles and chains, and your blood it must refuse to flow,

For you let this human race fall down so God-awful low!

This song is just a reminder to remind your fellow man

That this kind of thing still lives today in that ghost-robed Ku Klux Klan.

But if all of us folks that thinks alike, if we gave all we could give,

We could make this great land of ours a greater place to live.

Copyright © 1963; renewed 1991 Special Rider Music

http://lancefuhrer.com/dylan_emmett_till.htm

Bob Dylan sing "The Murder of Emmitt Till

The Death of Emmett Till

"Twas down in Mississippi no so long ago,

When a young boy from Chicago town stepped through a

Southern door.

This boy's dreadful tragedy I can still remember

well,

The color of his skin was black and his name was

Emmett Till.

Some men they dragged him to a barn and there they

beat him up.

They said they had a reason, but I can't remember

what.

They tortured him and did some evil things too evil

to repeat.

There was screaming sounds inside the barn, there

was laughing sounds out on the street.

Then they rolled his body down a gulf amidst a

bloody red rain

And they threw him in the waters wide to cease his

screaming pain.

The reason that they killed him there, and I'm sure

it ain't no lie,

Was just for the fun of killin' him and to watch him

slowly die.

And then to stop the United States of yelling for a

trial,

Two brothers they confessed that they had killed

poor Emmett Till.

But on the jury there were men who helped the

brothers commit this awful crime,

And so this trial was a mockery, but nobody seemed

to mind.

I saw the morning papers but I could not bear to see

The smiling brothers walkin' down the courthouse

stairs.

For the jury found them innocent and the brothers

they went free,

While Emmett's body floats the foam of a Jim Crow

southern sea.

If you can't speak out against this kind of thing, a

crime that's so unjust,

Your eyes are filled with dead men's dirt, your mind

is filled with dust.

Your arms and legs they must be in shackles and

chains, and your blood it must refuse to flow,

For you let this human race fall down so God-awful

low!

This song is just a reminder to remind your fellow

man

That this kind of thing still lives today in that

ghost-robed Ku Klux Klan.

But if all of us folks that thinks alike, if we gave

all we could give,

We could make this great land of ours a greater

place to live.

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAtillE.htm

Emmett Till, the only child of Louis Till and Mamie Till, was born near Chicago, Illinois, on 25th July, 1941. In August, 1955, Emmett, now aged 14, was sent to money, Mississippi to stay with relatives.

During the evening of 24th August, Emmett, a cousin, Curtis Jones, and a group of his friends, went to Bryant's Grocery Store in Money, Mississippi. Carolyn Bryant later claimed that Emmett had grabbed her at the waist and asked her for a date. When pulled away by his cousin, Emmett allegedly said, "Bye, baby" and "wolf whistled".

Bryant told her husband about the incident and he decided to punish the boy for his actions. The following Saturday, Roy Bryant and his half-brother, J. W. Milam, took Emmett from the house where he was staying and drove him to the Tallahatchie River and shot him in the head.

After Emmett's body was found Bryant and Milam were charged with murder. On 19th September, 1955, the trial began in a segregated courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi. In court Mose Wright identified Bryant and Milam as the two men who took away his nephew on the 24th August. Other African Americans also gave evidence against Bryant and Milam but after four days of testimony, the all white jury acquitted the men.

The Emmett Till case, publicized by writers such as William Bradford Huie, led to demonstrations in several northern cities about the way African Americans were being treated in the Deep South.

(1) Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi (1968)

I was now working for one of the meanest white women in town, and a week before school started Emmett Till was killed.

Up until his death, I had heard of Negroes found floating in a river or dead somewhere with their bodies riddled with bullets. But I didn't know the mystery behind these killings then.

When they had finished dinner and gone into the living room as usual to watch TV, Mrs. Burke called me to eat. I took a clean plate out of the cabinet and sat down. Just as I was putting the first forkful of food in my mouth, Mrs. Burke entered the kitchen.

"Essie, did you hear about that fourteen-year-old boy who was killed in Greenwood?" she asked me, sitting down in one of the chairs opposite me.

"No, I didn't hear that," I answered, almost choking on the food.

"Do you know why he was killed?" she asked and I didn't answer.

"He was killed because he got out of his place with a white woman. A boy from Mississippi would have known better than that. This boy was from Chicago. Negroes up North have no respect for people. They think they can get away with anything. He just came to Mississippi and put a whole lot of notions in the boys' heads here and stirred up a lot of trouble," she said passionately.

"How old are you, Essie?" she asked me after a pause.

"Fourteen, I will soon be fifteen though," I said.

"See, that boy was just fourteen too. It's a shame he had to die so soon." She was red in the face, she looked as if she was on fire.

When she left the kitchen I sat there with my mouth open and my food untouched. I couldn't have eaten now if I were starving. "Just do your work like you don't know nothing" ran through my mind again and I began washing the dishes.

I went home shaking like a leaf on a tree. For the first time out of all her trying, Mrs. Burke had made me feel like rotten garbage. Many times she had tried to instill fear within me and subdue me and had given up. But when she talked about Emmett Till there was something in her voice that sent chills and fear all over me.

Before Emmett Till's murder, I had known the fear of hunger, hell, and the Devil. But now there was a new fear known to me - the fear of being killed just because I was black. This was the worst of my fears. I knew once I got food, the fear of starving to death would leave. I also was told that if I were a good girl, I wouldn't have to fear the Devil or hell. But I didn't know what one had to do or not do as a Negro not to be killed. Probably just being a Negro period was enough, I thought.

I was fifteen years old when I began to hate people. I hated the white men who murdered Emmett Till and I hated all the other whites who were responsible for the countless murders Mrs. Rice (my teacher) had told me about and those I vaguely remembered from childhood. But I also hated Negroes. I hated them for not standing up and doing something about the murders. In fact, I think I had a stronger resentment toward Negroes for letting the whites kill them than toward the whites.

(2) Chicago Defender (1st October, 1955)

How long must we wait for the Federal Government to act? Whenever a crisis arises involving our lives or our rights we look to Washington hopefully for help. It seldom comes.

For too long it has been the device, as it was in the Till case, for the President to refer such matters to the Department of

Justice.

And usually, the Department of Justice seems more devoted to exploring its lobos for reasons why it can't offer protection of a Negro's life or rights.

In the current case, the Department of Justice hastily issued a statement declaring that it was making a thorough investigation to determine if young Till's civil rights had been violated.

The Department evidently concluded that the kidnapping and lynching of a Negro boy in Mississippi are not violations of his rights.

This sounds just like both the defense and the prosecution as they concluded their arguments by urging the jury to "uphold our way of life."

The trial is over, and this miscarriage of justice must not be left unavenged. The Defender will continue its investigations, which helped uncover new witnesses in the case, to find other Negroes who actually witnessed the lynching, before they too are found in the Tallahatchie river.

At this point we can only conclude that the administration and the justice department have decided to uphold the way of life of Mississippi and the South. Not only have they been inactive on the Till case, but they have yet to take positive action in the kidnapping of Mutt Jones in Alabama, who was taken across the state line into Mississippi and brutally beaten. And as yet the recent lynchings of Rev. George Lee and LaMarr Smith in Mississippi have gone unchallenged by our government.

The citizens councils, the interstate conspiracy to whip the Negro in line with economic reins, open defiance to the Supreme Court's school decision - none of these seem to be violations of rights that concern the federal government.

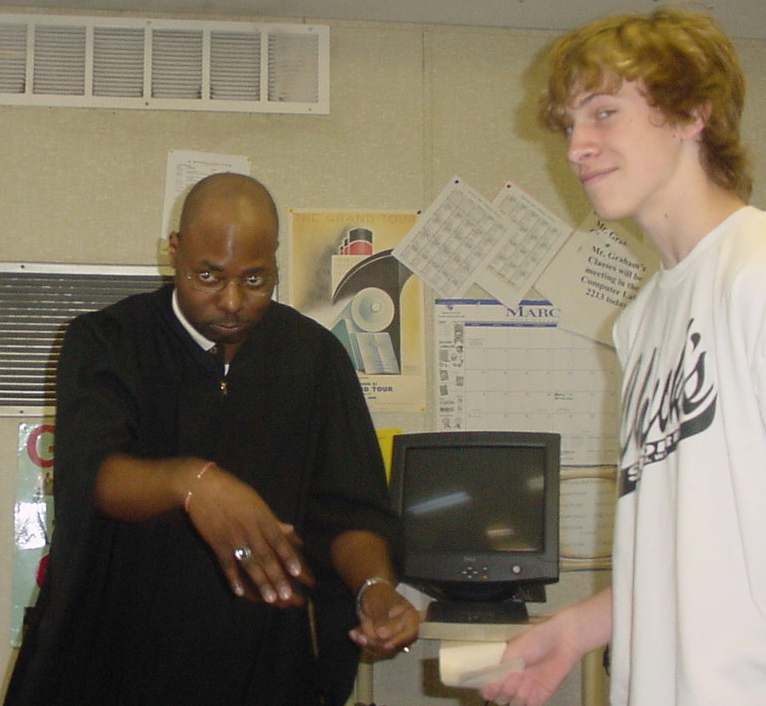

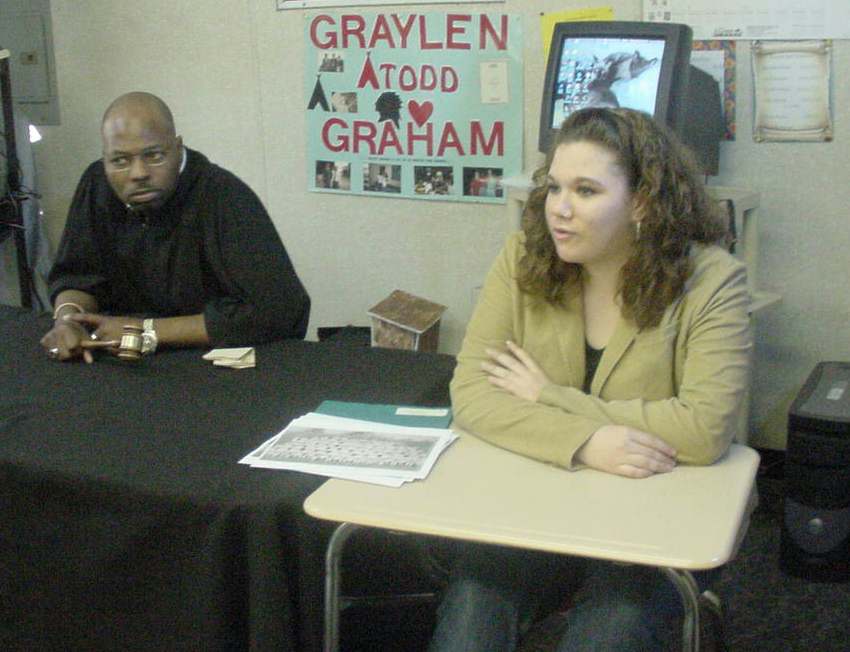

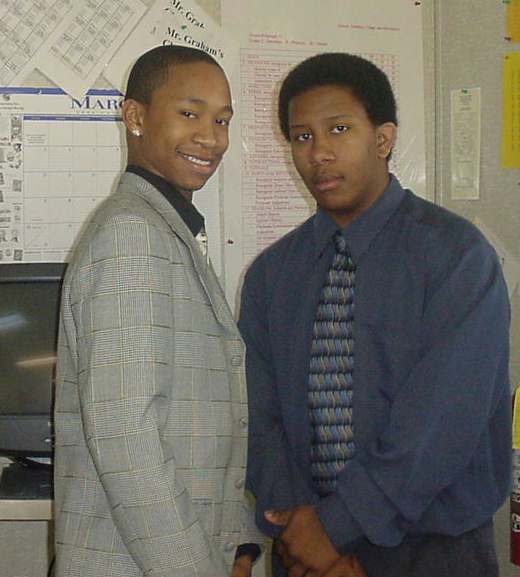

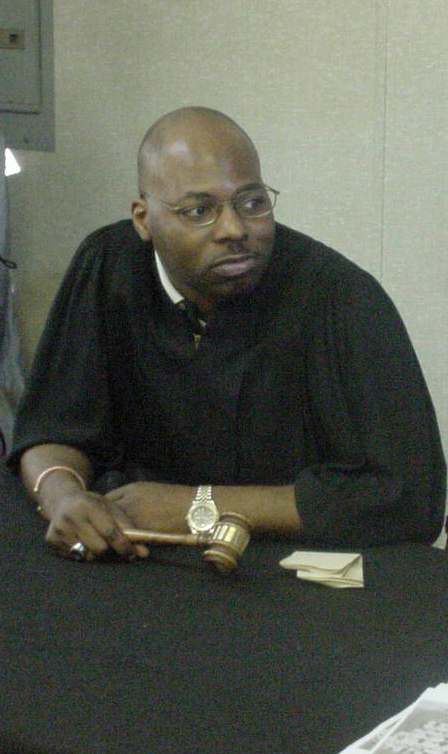

Student Pictures of The Emmett Till Trial

![]()

|

|